A Cultural Journey Through Hawaiian Royal Symbolism

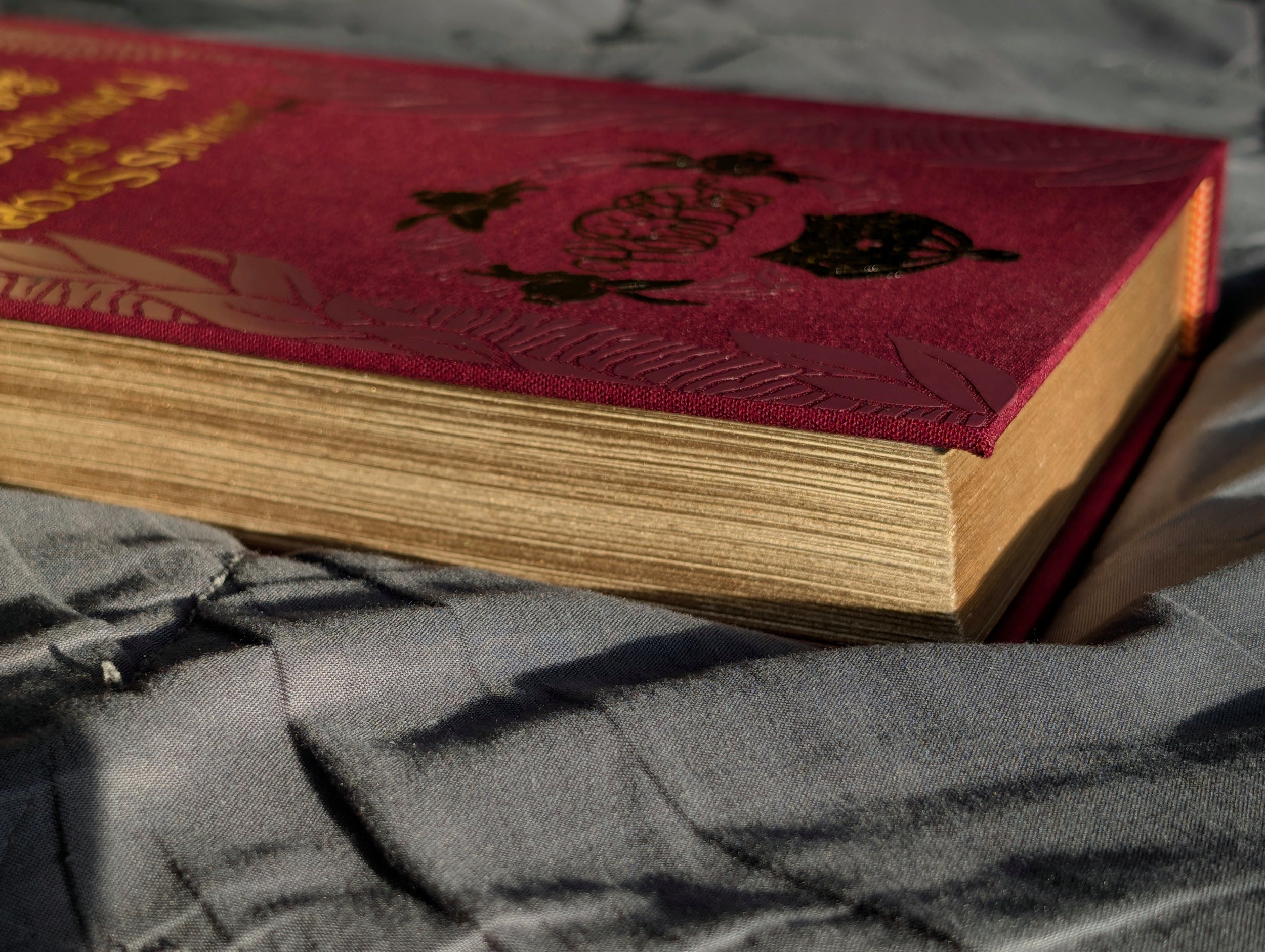

When approaching the rebinding of Queen Liliʻuokalani's seminal work "Hawaii's Story by Hawaii's Queen" for the Pacific Islander Student Association at Montana State University, the research process became as important as the final artistic result. This educational journey through Hawaiian royal symbolism demonstrates how extensive cultural research can guide respectful artistic choices, particularly for non-Hawaiian artists working with Indigenous cultural elements.

As someone with an MLIS, I was excited to put my research training to work on something deeply meaningful. The challenge was clear: how to honor the last reigning monarch of the Hawaiian Kingdom through visual design that felt authentic to her legacy and respected Hawaiʻi from a non-colonist and non-tourist perspective. The answer lay in a dedicated afternoon of careful research, consultation with Hawaiian cultural sources, and deep respect for the ongoing Hawaiian sovereignty movement that views Queen Liliʻuokalani's story as a living document of resistance (Liliʻuokalani, 1898).

The Royal Seal

Queen Liliʻuokalani's royal seal, officially known as the Hawaiian Kingdom Coat of Arms, revealed itself as more than decorative heraldry. Adopted in 1845 during King Kamehameha III's reign, the seal carries profound spiritual and political significance that connects directly to contemporary Hawaiian sovereignty claims (Kamehameha Schools, 2024).

The quartered shield tells the story of the Hawaiian nation through symbolic language. Eight alternating white, red, and blue stripes represent both the Hawaiian flag and the eight inhabited islands of the Kingdom, while the sacred Pūloʻuloʻu symbols (kapa-covered balls atop sticks) represent the kapu system that governed chiefly authority (Images of Old Hawaiʻi, 2024). Two male figures in magnificent feather cloaks serve as supporters, representing the sacred royal twin brothers Kameʻeiamoku and Kamanawa who helped Kamehameha I unite the islands.

My research revealed that these were encoded messages of sovereignty and divine authority. The red and yellow colors exclusively associated with aliʻi (chiefs) carried spiritual power (mana), while the crown ornamented with kalo (taro) leaves connected the monarchy to the very foundation of Hawaiian sustenance and survival (Ho'okuleana Blog, 2012).

Most significantly, the royal motto "Ua Mau ke Ea o ka ʻĀina i ka Pono" translates to "The life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness" — words that continue to resonate in contemporary Hawaiian sovereignty movements. Understanding this context transformed my approach from decorative borrowing to respectful acknowledgment of ongoing political and cultural significance.

While significant, the seal used on the cover of the book is Queen Liliʻuokalani's monogram with a crown, as the royal seal was too complicated for this. Plus, the book itself is written by her, and I wanted to honor that.

ʻIlima flowers

While researching authentic Hawaiian floral symbolism for the spine and cover lei designs, I discovered the profound significance of ʻilima flowers in Hawaiian royal culture. The ʻilima (Sida fallax), officially designated as Oʻahu's island flower in 1988, carries deep cultural meaning that extends far beyond its delicate beauty (State Symbols USA, 2018).

What struck me immediately was learning that ʻilima lei were among the most precious in Hawaiian culture because of their labor-intensive creation process. A single-strand ʻilima lei requires anywhere from 500 to 1,000 individual flowers, each carefully strung together (Native Hawaiian Garden, 2024). The flowers were traditionally harvested in the late afternoon or evening and strung together the following morning, making each lei a significant investment of time and devotion.

The cultural significance of ʻilima extends deep into Hawaiian royal traditions. Written records indicate some debate about whether ʻilima lei were reserved exclusively for royalty, but their golden-yellow color held particular significance for the aliʻi (Native Hawaiian Garden, 2024). The flowers were so valued that ʻilima was one of the few native plants Hawaiians purposely cultivated, with specific varieties like "ʻilima lei" grown around homes for their particularly beautiful flowers (Bishop Museum, 2024).

In Hawaiian spiritual traditions, ʻilima carries profound meaning beyond ornamentation. The flowers have been used medicinally as the first medicine given to babies—a mild laxative administered with great care. Hiʻiaka, the goddess of medicine in Pele's family, used ʻilima in her healing practices, connecting the flower to divine healing power (Bishop Museum, 2024). The plant's hardy nature, thriving from sea level to over 6,500 feet elevation in various soil conditions, made it a symbol of resilience and adaptability.

The connection between ʻilima and the aliʻi class becomes even more meaningful when considering the flower's two distinct growth forms. ʻIlima papa grows prostrate along coastal areas, representing groundedness and foundation, while ʻilima kū grows upright into shrubs, symbolizing strength and elevated status (Maui Ocean Center, 2024). This duality perfectly mirrors the dual nature of Hawaiian royalty—rooted in the land yet elevated above it.

For my binding design, incorporating ʻilima patterns felt essential to honoring Queen Liliʻuokalani's connection to authentic Hawaiian royal traditions rather than tourist representations. The tedious process of creating ʻilima lei, requiring hundreds of delicate flowers, mirrors the careful research process needed to respectfully represent Hawaiian culture.

Crown flowers

Building on my ʻilima research, I also investigated Queen Liliʻuokalani's documented preference for Pua Kalaunu (Crown Flowers), which opened another window into her personal world while revealing sophisticated symbolism embedded in Hawaiian royal traditions (Kakou Collective, 2024; Lei Poina'ole Project, 2024). This represented a profound connection between the monarch and a flower whose very structure mirrored her royal authority.

Traditional Hawaiian chant documents this relationship: "'O ka pua kalaunu, he pua kaulana iā Lili'uokalani. 'Ike ho'i ka nani o ia pua lā, 'elima mau kihikihi i paa 'ia ke kahua ola o ia ali'i nei." The translation reveals the depth of meaning: "The Crown Flower was Queen Liliʻuokalani's favorite flower. Observe the beauty of this flower with five edges holding a strong foundation of this chiefess" (Lei Day Organization, 2024).

The research uncovered layers of symbolism in the Crown Flower's five-pointed crown structure. Each bloom literally crowns itself with royal authority, while the flower's introduction to Hawaiʻi during the monarchy period parallels the complex cultural negotiations that defined 19th-century Hawaiian society (BEHawaii, 2024). Purple Crown Flowers (pua kalaunu poni) represent royalty and nobility, while white varieties symbolize purity and are traditionally used in bridal lei because of their association with being "queen for the day."

Hawaiian Quilting

My research into Queen Consort Kapiʻolani's quilt patterns unveiled Hawaiian quilting as a sophisticated form of cultural storytelling that carries deep spiritual and political significance. The specific pattern "The Fans and Feather Banner [kāhili] of Kapi'olani" created by Mary Kauhoanoano represents something far more complex than decorative needlework—it encodes the royal relationship between the two queens and the cultural values they championed (Historic Hawaii Foundation, 2021).

The fan motifs in these quilts specifically reference Queen Consort Kapiʻolani's personal quilt, serving as a metaphor for her mana (spiritual life force) and royal femininity. These crescent-shaped fans were "personal articles associated with the chiefly class, beautifully fashioned from plaited fibers of various plants," making them intimate symbols of royal identity rather than generic decorations (Historic Hawaii Foundation, 2021).

The feather patterns (kāhili) carry even deeper significance. Kāhili were sacred feather standards that were "treated as family members, imbued with the owner's spiritual power" and carried by attendants to signify the presence of chiefs (Kamehameha Schools, 2024). Each kāhili had personal names and caretakers (kahu), enhancing the aliʻi's spiritual protection and connecting to the traditional role of feathered standards in warfare and ceremony.

What struck me during my research was learning about the relationship between Queen Liliʻuokalani and Queen Consort Kapiʻolani, which adds personal dimension to these symbols. As sisters-in-law with a close, supportive relationship, they traveled together to Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee in 1887, visited the Kalaupapa Leprosy Settlement in 1884, and shared a commitment to Hawaiian cultural preservation (Unofficial Royalty, 2024). Their joint philanthropic work and shared artistic patronage influenced Hawaiian quilting traditions that honored both women as cultural guardians.

Hawaiian quilts were traditionally imbued with the quilter's mana, making them spiritual journeys as much as artistic expressions (Wikipedia, 2024). The quilting process itself follows specific cultural practices: patterns cut from fabric folded in eighths create radially symmetric designs, quilted with "echo" stitching that follows contours like ocean waves. Understanding this spiritual dimension was crucial for respectful representation in my binding design.

Cultural Protocols

Perhaps the most critical aspect of my research involved understanding contemporary Hawaiian perspectives on cultural appropriation versus appreciation. The Native Hawaiian Intellectual Property Rights Working Group, chaired by Kumu Hula Vicky Holt Takamine, provides clear guidance through documents like the Paoakalani Declaration (2003), which asserts Native Hawaiian collective intellectual property rights and the "collective right of self-determination to perpetuate our culture under threat of theft and commercialization" (Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation, 2024).

My hours of research revealed that Hawaiian cultural practitioners distinguish between sacred cultural elements and general cultural sharing, with royal symbols requiring special consideration. Bishop Museum guidelines emphasize that royal Hawaiian symbols like kāhili (feather standards), ʻahu ʻula (feather cloaks), and royal insignia are "sacred symbols of Hawaiian aliʻi representing sanctity and mana of chiefs" that require appropriate context and consultation (Kamehameha Schools, 2024).

Contemporary Hawaiian cultural advisor Kanoelani Davis explains that "motifs and patterns in Hawaiian culture identify a person, place, or thing and are a form of communication... They are often associated with a particular family" (Wanderful Blog, 2024). This understanding transformed my approach from decorative borrowing to respectful cultural dialogue.

The key principles that emerged from Hawaiian cultural practitioners include educational responsibility ("do your research, and know what you're wearing comes from"), authentic relationships that are "mutually beneficial and respectful," and community consultation before using cultural symbols (Wanderful Blog, 2024). The distinction between educational use and commercial exploitation became central to the ethical framework for my project.

My research also revealed how the 1893 overthrow of Queen Liliʻuokalani continues to impact contemporary cultural practices. The systematic suppression of Hawaiian language, hula, and traditional practices following the overthrow means that every respectful use of Hawaiian cultural symbols today participates in ongoing cultural recovery and resistance (Ballard Brief, 2024).

Historical Context

"Hawaii's Story by Hawaii's Queen," published in 1898, emerged from my research not as historical artifact but as living document of resistance. Written during Queen Liliʻuokalani's residence in Boston while seeking congressional support for restoring Hawaiian sovereignty, the book represents "possibly the most important work in Hawaiian literature" and remains foundational to contemporary sovereignty movements (Project MUSE, 2024).

The book's significance extends beyond its content to its role in Hawaiian cultural preservation. As the only autobiography written by a Hawaiian monarch, it provides a firsthand account of the illegal overthrow that continues to inform Hawaiian sovereignty claims. My research revealed how Hawaiian scholars and cultural practitioners view the Queen's memoir as essential reading for understanding the illegal nature of the Hawaiian Kingdom's overthrow and the ongoing struggle for sovereignty (Wikipedia, 2024).

This contemporary relevance shaped my entire approach to the rebinding project. Rather than treating the book as a historical curiosity, my research emphasized its continued importance in Hawaiian political and cultural discourse. The visual design needed to honor not just the historical Queen Liliʻuokalani but her ongoing significance in Hawaiian resistance and cultural preservation.

Conclusion

This research demonstrates how cultural sensitivity in art requires deep engagement with both historical context and contemporary perspectives. My MLIS training proved invaluable in navigating the complex web of Hawaiian cultural sources, from academic databases to contemporary Hawaiian cultural organizations. The hours I spent researching revealed that respectful cultural representation demands ongoing relationship-building rather than one-time consultation, authentic engagement with Hawaiian communities, and recognition of the political dimensions of cultural symbols. My final design approach honored Queen Liliʻuokalani's legacy through careful attention to the symbolic meanings embedded in her royal seal, personal connections to Crown Flowers, and the sophisticated cultural storytelling traditions of Hawaiian quilting. Given that most all members of the student association became emotional at looking at it, it made the time more than worth it.

For artists working across cultural boundaries, this research model offers a pathway toward respectful cultural engagement that honors the complexity and ongoing significance of Indigenous cultural traditions. The goal is not to avoid cultural exchange but to ensure such exchange supports Indigenous communities and respects the sophisticated cultural knowledge systems that give symbols their meaning.

References

Andrea Pro. (2024). Monarchs love pua kalaunu. Andrea Pro, Printmaker. Retrieved from https://andreapro.com/product/monarchs-love-pua-kalaunu/

Ballard Brief. (2024). Struggle for Hawaiian cultural survival. Brigham Young University. Retrieved from https://ballardbrief.byu.edu/issue-briefs/struggle-for-hawaiian-cultural-survival

BEHawaii. (2024). Pua kalaunu (crown flower). Retrieved from https://www.behawaii.org/blog/pua-kalaunu-crown-flower

Bishop Museum. (2024). Ethnobotany database: ʻIlima. Retrieved from http://data.bishopmuseum.org/ethnobotanydb/ethnobotany.php?b=d&ID=ilima

Historic Hawaii Foundation. (2021). Celebrating quilting & the women of the Hawaiian monarchy. Retrieved from https://historichawaii.org/2021/03/19/quiltshonoringwomenofhawaiianmonarchy/

Ho'okuleana Blog. (2012). Hawaiian coat of arms and seal. Retrieved from http://totakeresponsibility.blogspot.com/2012/10/hawaiian-coat-of-arms-and-seal.html

Images of Old Hawaiʻi. (2024). Hawaiian coat of arms and seal. Retrieved from https://imagesofoldhawaii.com/hawaiian-coat-of-arms-and-seal/

Kakou Collective. (2024). Pua kalaunu: The crown flower's place in lei making traditions of Hawai'i. Retrieved from https://kakoucollective.com/blogs/craftingmoolelos/pua-kalaunu

Kamehameha Schools. (2024). Coat of arms of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi. Ka'iwakīloumoku - Hawaiian Cultural Center. Retrieved from https://kaiwakiloumoku.ksbe.edu/article/heritage-center-coat-of-arms-of-the-kingdom-of-hawaii

Kamehameha Schools. (2024). Kāhili: Feather standards. Ka'iwakīloumoku - Hawaiian Cultural Center. Retrieved from https://kaiwakiloumoku.ksbe.edu/article/essays-kaahili-feather-standards

Lei Day Organization. (2024). Ke kaona o ka lau nahele o Liliʻulani. Retrieved from https://www.leiday.org/ke-kaona-o-ka-lau-nahele-o-lili%CA%BBulani/

Lei Poina'ole Project. (2024). Pua kalaunu. Retrieved from https://leipoinaoleproject.org/flowers/crown-flower

Liliʻuokalani. (1898). Hawaii's story by Hawaii's queen. Boston: Lee and Shepard.

Maui Ocean Center. (2024). ʻIlima. Retrieved from https://mauioceancenter.com/plants-life/ilima/

Native Hawaiian Garden. (2024). ʻIlima. Retrieved from https://www.nativehawaiiangarden.org/flowering-plants/ilima

Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation. (2024). Launch of Resolution 108 Native Hawaiian intellectual property working group. Retrieved from https://nativehawaiianlegalcorp.org/launch-of-resolution-108-native-hawaiian-intellectual-property-working-group/

Project MUSE. (2024). The queen writes back: Lili'uokalani's Hawaii's story by Hawaii's queen. Johns Hopkins University Press. Retrieved from https://muse.jhu.edu/article/185520/summary

State Symbols USA. (2018). Pua ʻilima. Retrieved from https://statesymbolsusa.org/pua-ilima

Unofficial Royalty. (2024). Kapiʻolani, queen consort of the Hawaiian Islands. Retrieved from https://www.unofficialroyalty.com/kapi%CA%BBolani-queen-consort-of-the-hawaiian-islands/

Wanderful Blog. (2024). What is cultural appropriation and how can travelers avoid it? Retrieved from https://blog.sheswanderful.com/what-is-cultural-appropriation-and-how-can-travelers-avoid-it/

Wikipedia. (2024). Hawaiian quilt. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hawaiian_quilt

Wikipedia. (2024). Liliʻuokalani. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lili%CA%BBuokalani